Peering through the paint – Revealing the Lucia Master

Sjors Nab won the 2025 Humanities RMA Thesis Prize for his technical art-historical research on the Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy. Layer by layer, he explored the paintings of this fifteenth-century Flemish painter, whose real name remains unknown. The Centre for Digital Humanities spoke with him about his research and the techniques he used.

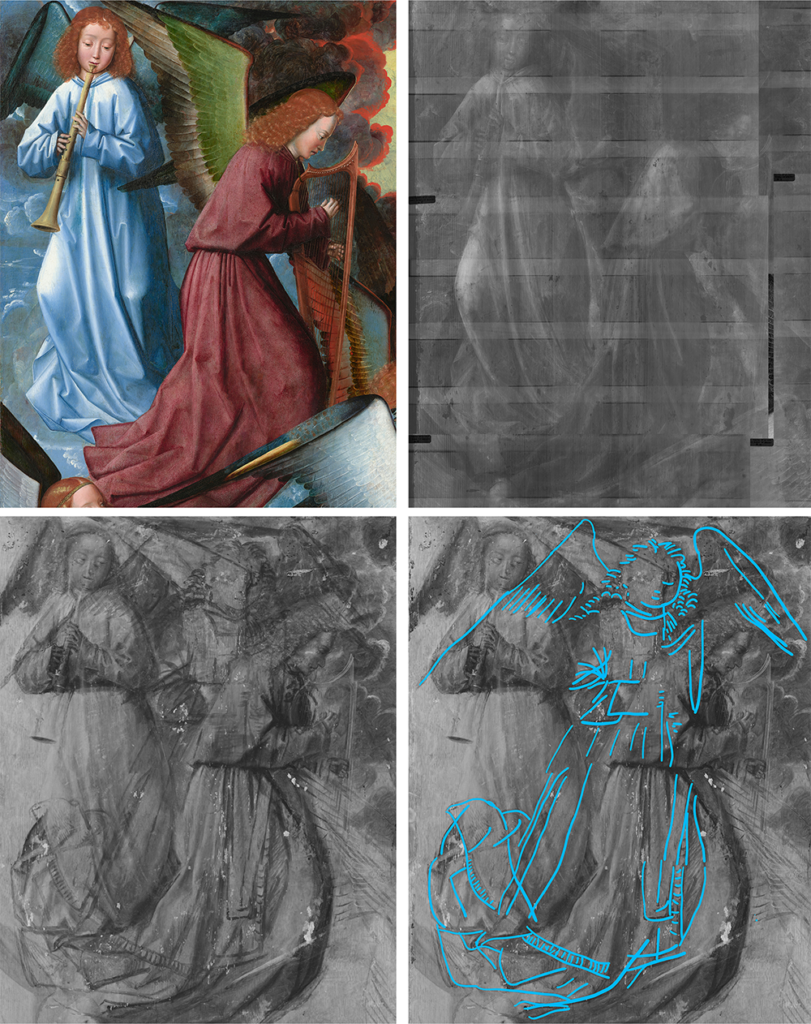

When Sjors Nab was staring at an infrared image of a fifteenth-century painting at three in the morning, he suddenly spotted what looked like a medieval smiley face in one of the underlayers: a simple circle with two eyes, a nose, a mouth, and two big ears. “Someone drew that 550 years ago in the spot where an angel was supposed to be,” Nab laughs. “Later, paint was applied over it. It was never meant to be seen. And suddenly, I’m looking right at it. That’s still amazing.”

You call yourself a technical and digital art historian. What does that mean?

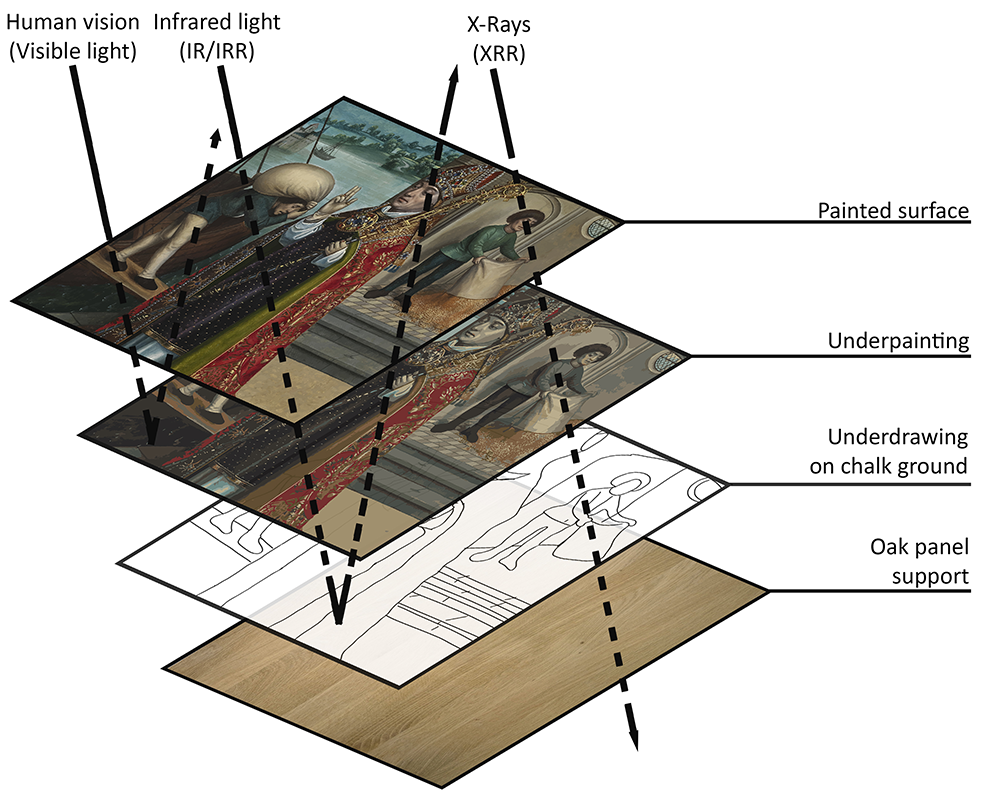

“I study paintings using techniques such as infrared and X-ray imaging.” He shows a series of images of the same painting. “Look — here the arch runs slightly higher than in the underpainting, and here the water is painted a bit lower than in the underdrawing.”

You studied the paintings of the Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy. What drew you to him?

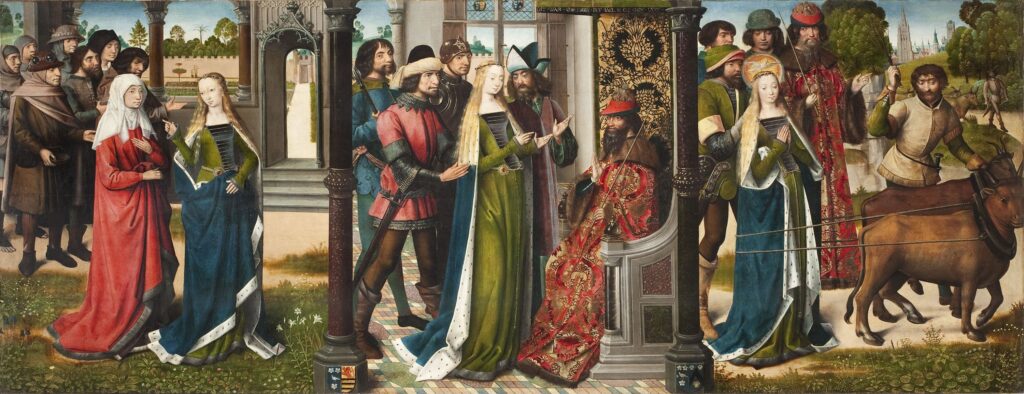

“The Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy — not exactly a name that rolls off the tongue,” Nab laughs, “He’s named after the painting The Legend of Saint Lucy. This master was enormously successful in his day and worked for patrons across Europe. Yet in recent decades he has often been dismissed as a copyist or craftsman, not a true artist.”

“Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, Bosch, and Bruegel are the big names of fifteenth-century Flemish painting. But I wondered: are they so well-known because they were truly the best, or simply because their names survived? More than three-quarters of the paintings from that period can no longer be linked to a specific painter’s name.”

“Of the ten largest surviving Flemish panel paintings from the fifteenth century, two are by the Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy — or, in short, the Lucia Master. This painter, who hasn’t always been highly regarded in the literature, had a remarkably large production. I wanted to know: do the seventy paintings attributed to him actually belong together? What remains of that corpus if I look purely at the technical aspects of his painting style?”

How did you manage to collect all those works, including the infrared and X-ray images?

“That involved a lot of negotiating and pleading. I spent the first month doing nothing but emailing. Luckily, I had the full support of my thesis supervisor, Daantje Meuwissen, who has a lot of experience with this kind of research. My previous internship at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels was a key advantage. I had contact with curators at the Prado in Madrid and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. The Prado curator found my research interesting, which meant I could tell other museums: the Prado is already on board! Another advantage was that I was willing to publish my thesis under embargo. In the end, I was surprised by how open most institutions were to collaboration. After all, I was just a master’s student emailing museums around the world.”

What do these techniques reveal?

“An X-ray allows you to see through the entire painting, including the wooden panel support. Infrared images show the underdrawing best. I look from back to front: the drawing was made directly on the panel, then came the underpainting, followed by a first layer of paint to define light and shadow, and finally ten to twelve layers of oil paint.”

“To compare these layers accurately, you need the highest-quality images available. The seventy works I collected varied enormously in quality — from state-of-the-art research photos to a single black-and-white image from 1910. Sometimes you need to draw a few guiding lines. Mostly, it’s a matter of looking for a very long time, comparing all those little squiggles. It’s a kind of guided meditation, really.”

And what have you learned from looking that way?

“The changes between layers reveal how a painter worked. Dieric Bouts, for example, we jokingly call the tap-dance master: in his underdrawings you sometimes see eight hundred feet side by side. The Lucia Master, by contrast, followed a very refined process of gradual improvement — an arm becoming slightly thinner with each layer, tiny dots and strokes to indicate shadow. You see continuous small, inventive adjustments. That’s what I call a creative process, not merely copying.”

Are all those works rightly attributed to him?

“I now have a good sense of his working method and noticed a technical consistency throughout. You can even see it in his hesitations: the Lucia Master is always fiddling with the little roof above Mary and Child — the arch rises and falls again. So most attributions in art history turned out accurate. But there are two important works that, in my view, don’t fit. Their underdrawings are extensively revised with five or six stages and with endless charcoal reworking. In his other works, there are always just one or two stages. That process is completely different from his other paintings.”

The thesis prize jury wrote: ‘The significance of his study extends beyond this particular painter, because his method within technical art history can also be applied to other oeuvres.’ What does your approach add to existing methods?

“In technical art history, there’s a strong drive toward the newest technologies and highest resolutions. That yields excellent results, but such projects cost millions. I believe you can also achieve a great deal using existing materials if you systematically bring them together and study them consistently.”

What are your next plans?

“I’m going to work as lab manager at Utrecht University’s ArtLab, an innovative research and teaching centre for this kind of study. We’ll be collaborating closely with museums and heritage institutions to tackle their research questions.”

Read more about the Humanities Thesis Prize winners

Read more about the ArtLab