Interview with Suzanne Ros, winner of the Digital history thesis award

During her research into the term ‘Anthropocene’ for her bachelor’s thesis in history, Suzanne Ros discovered that the subject was much larger than she had expected. She decided to dive into digital methods that could help her with her analysis, and she taught herself Python through YouTube videos. Successfully. She won the recently created thesis award for digital history.

Suzanne Ros is sitting in a cabin in Patagonia when the Centre For Digital Humanities speaks to her. She is taking a well-deserved 6 month break after completing her bachelor’s degree in German, bachelor’s degree in History and co-writing a scientific article with her second supervisor. Dogs bark in the background, as she, heavily dressed – ‘It’s cold here!’ – talks to us through her phone’s video function and explains about her research.

First of all, can you explain what exactly the Anthropocene is?

‘The term Anthropocene is usually used to refer to the age of humankind, but it actually revolves around the new role that people have taken on within the ecosystems of the earth. In recent times, human beings have changed the ecosystems so much, becoming such a significant and unavoidable force, that the Anthropocene has been proposed as a new geological era. There is still a lot of discussion within geology about when this era started and therefore it is not yet an official term. Some mention the industrial revolution and others say it was much earlier.’

How did you become interested in the term?

‘When I wrote my thesis for my bachelor German, about nature poetry, I often came across the German word ‘Anthropozän’ in the reviews. I noticed that the term was used just about everywhere without being properly explained. My supervisor at the time said I’d better avoid the term so I wouldn’t have to get involved in the debate. That really just triggered me. When I started reading more about the term, I realized that it was actually a very good subject for my history thesis.’

What was your research question?

‘How did the concept of the Anthropocene arise, how did it migrate from geology to other scientific disciplines, and how did it become politicized in public discourse? I focused on the Dutch public debate by looking at Dutch quality newspapers and how the term appeared in these sources’.

What digital methods did you use?

‘My thesis has become a collection of quantitative and qualitative analyses. With the help of digital methods I mainly researched the migration of the term. First, I looked at the rise of the term with Google Ngram Viewer, a function of Google that allows you to search all of Google’s digitized resources. The feature automatically creates a chart based on the word(s) you search for. Through Ngram, I could establish very nicely when the term first came up and how often it was used. However, when using this function you should keep in mind that errors are likely to occur, because the application uses optical character recognition, meaning that an image is converted into text. But it’s a fun and accessible starting point.

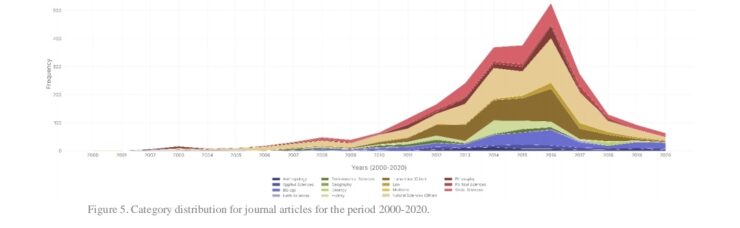

Then I looked at the migration of the term Antropocene, and various alternative spellings of the word, in a dataset from JSTOR. JSTOR offers a service, Data for Research, with which you can compile and retrieve your own dataset. They provided a dataset of 5.483 sources consisting of articles, book chapters and research reports. JSTOR ensures that the different data is collected into one file and that it is ‘clean’ data – i.e. stripped of incorrect information, duplicates, empty fields, etc. – so that you can use it right away.

For the purpose of dividing the sources into different scientific disciplines, I wrote a tailor-made code in Python. I taught myself how to program with the help of YouTube videos and free online courses. And I have people around me who can program, so I could always ask them questions.’

Where there any surprising results?

‘The term Anthropocene was mainly used in natural science articles at the beginning of the period, which makes sense, but it soon migrated to other disciplines. Thus, the geological term was picked up and used in disciplines such as history and sociology. I expected the term to stick more to geology. What was also nice to see, was that the frequently used terms that occurred around Anthropocene matched the disciplines. For example, in history you often saw the terms ‘politics’, ‘history’ and ‘culture’. In geology technical associating terms such as ‘ecosystems’ were more common. I also found out that people use the term for their political messages; as a call to better take care of the climate, or even as a cry of despair in this regard.’

What was the biggest challenge in combining historical research and digital methods?

‘My main challenge was not being able to brainstorm with someone who also used digital methods. My supervisors were very good, but they were not specialized in digital methods, which made it difficult for them to properly guide me at times. I could not ask them practical questions about error messages in code, for example. My fellow students weren’t really interested in digital methods either. I was referred to someone from the University Library, but before I got the answer back, I was already working on something else. Everyone is very busy, which can make you feel a bit uncomfortable to ask questions. It would be useful if we as students know better who we can approach and what questions we could ask.’

What are you most proud of?

‘This thesis brought about a lot for me. I was very happy with my grade, a nine. My second reader then approached me to ask whether I would be interested in writing an article with him because he liked my thesis so much. That was a great honor and kept me busy from September to November 2021. My second supervisor is still writing and editing; after completion, the article will be published.’

Read more about the Digital history thesis award here and find the news item about Suzanne Ros winning the award here.