Looking for patterns in readers’ reviews of translated books using DIOPTRA-L

What do English readers expect from translated literature? And how about the Dutch? Professor Haidee Kotze and her research team used big data to look for patterns in the way that ordinary readers review translated literature. Together with the Digital Humanities Lab they developed DIOPTRA-L, a corpus with 280.000 reviews of more than 150 books in 8 different languages.

What is this research project about?

Haidee Kotze: ‘Most of the research on readers’ views of translated literature focuses on professional reviewers. This project arose from our curiosity about real readers and what they think about literary translations. Are they aware of the fact that they are reading a translation? Does it matter to them? Do they notice things about the translation, and if so, what kind of things do they notice? And can we find patterns in their comments that tell us something about how translations are conceptualized by their readers?’

Why did you approach the Digital Humanities Lab (DH Lab)?

‘There is a lot of theorization about the different ways you can translate and what audiences might expect, need or like. But there is not a lot of empirical research on how the readers themselves experience translated texts. There has been some research using surveys, eye-tracking experiments and ethnographical approaches – and this is all rich data – but it focuses on very specific situations. My colleague Gys-Walt van Egdom and I share an interest in how user-generated content can be used to study the responses of ordinary readers to translations. And we wanted to see if we could develop a computational approach and use big data to look for bigger patterns in these responses.’

What kind of tool did you develop with the DH Lab?

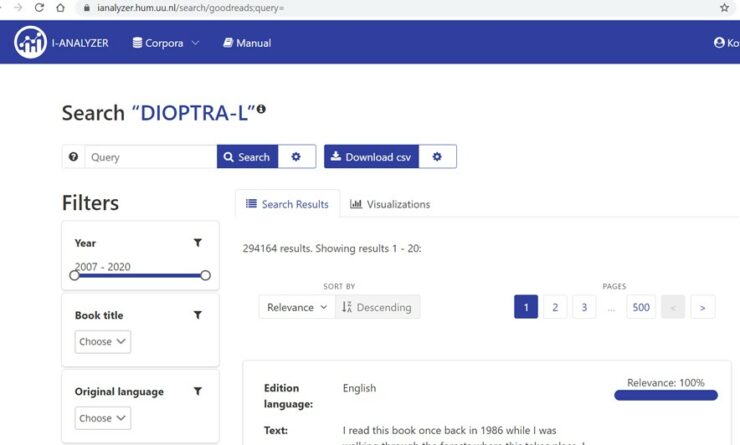

‘Together with the DH Lab we created the DIOPTRA-L (Digital Opinions on Translated Literature) database that now contains about 280.000 reviews from the Goodreads website – around 33 million words of reviews of books that have been translated to and from 8 languages. And it is growing. It is hosted in I-Analyzer, which is also developed by the DH Lab, and has a really user-friendly interface. This tool made it possible for us to do the kind of work that we had conceptualized, but weren’t quite sure on how to go about.’

What is the most interesting conclusion from this research?

‘That it was possible to use this big dataset and different computational methods to identify what we call ‘cognitive-evaluative templates’. With that I mean the most important concepts that people use when they talk about or evaluate translated books. And even more importantly, we were able to show that these ‘templates’ are partially similar for different translation directions, but also partially different.’

“English readers absolutely have an expectation of fluency. Words like ‘stilted’, ‘clumsy’ or ‘awkward’, occur all the time in their reviews.”

Did the research outcomes surprise you?

‘We did find empirical support for some common ideas in translation theories in our analysis of the readers’ comments, but there were also completely unexpected findings. The data gave a really rich perspective on how readers engage with translated literary texts.’

Can you give an example of where the theory did and didn’t match with the actual comments?

‘In translation research there is a widespread assumption that English readers have an expectation of fluency for translated texts. That means that they expect a book translated from another language into English to read as if it was originally written in English; they expect the style to match what they are familiar with. And we found that this is really the case. When we compared reviews of texts translated from other languages into English with reviews of translations form English into other languages, we see very clearly that English readers absolutely have an expectation of fluency. Some words, like ‘stilted’, ‘clumsy’ or ‘awkward’, occur all the time in their reviews. That’s really different compared to reviews of translations that go in the opposite direction. You don’t really see for example French or Italian readers commenting on this idea of fluency so much. An unexpected finding was that there was a link between how often translation is mentioned, and the star ratings given to books: more mentions of translation are correlated with lower star ratings, in reviews of translated books. It’s almost as though the fact that a book is translated is treated as a ‘scapegoat’ for disliking a book.’

Did DIOPTRA-L lead to new research questions?

‘Absolutely. That is one of the things that makes me incredibly happy about this project. We didn’t just get to answer the questions that we have, but we have also created a resource that is there for all sorts of other research questions. So anybody who is interested in readers’ reviews of translations or of literary texts in general, can use this database. It is designed for quantitative research, but you can also use it in a really qualitative way by downloading reviews on a particular book and analyzing those in an almost close-reading way.’

What is the biggest challenge in working with quantitative methods?

‘It is very challenging to extend quantitative methods to questions of meaning. How do you turn a question that is all about a phenomenon that is not inherently quantitative into something that is quantifiable in your corpus data? That’s a real challenge. And to make sure that you’ve built a solid conceptual bridge between your more abstract question and the actual quantitative method.’

Will you start looking for the ‘why’ behind these patterns in the future?

‘Yes absolutely. This method doesn’t answer the ‘why’. And, as with most research, you end up with more questions in the end, and an awareness of all the limitations of your data and method. So after this quantitative analysis you need to start thinking about what sort of data or method you need to answer all these new questions. That’s the next step.‘

Haidee Kotze is Professor Translation Studies at Utrecht University.